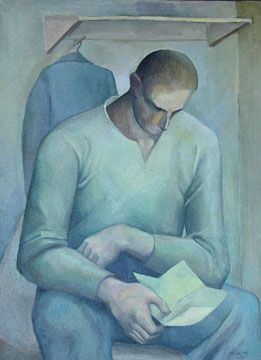

The Prophet Elijah Fed by the Raven, Icon, Byzantine tradition.

Some fatigue does not come from lack of sleep but from carrying too much for too long — work that never slows, worries that linger, responsibilities that follow us into the night. In the Gospel of the Transfiguration, Jesus leads Peter, James, and John up a mountain, away from the noise and weight of daily life, and for a brief moment they glimpse His glory. Then the voice from the cloud speaks: “This is my beloved Son… listen to Him.” Lent invites us into that same movement — not to escape life, but to see it clearly again. Like Elijah discovering God not in wind or fire but in a gentle whisper, we learn that the spiritual life begins in quiet listening. We do not remain on the mountain; we return to ordinary routines. Yet faith is formed there, in small faithful moments: Sunday Mass, a simple Lenten sacrifice, a decade of the rosary, a quiet prayer before sleep, a hidden act of kindness. Holiness is not built in grand gestures but in many small offerings of love, gathered day by day — like the quiet unfolding of Bach’s Cello Suites, where simplicity becomes depth and repetition becomes beauty. As life grows noisy again, the voice from the cloud still speaks: listen to Him. Give Him one small moment. He will do the rest •

Johann Sebastian Bach’s Cello Suites are among the most intimate works in all of classical music. Written for a single instrument, they reveal how simplicity can unfold into surprising depth: a single melodic line becomes prayer, meditation, and quiet conversation with the soul. Their beauty does not overwhelm; it emerges slowly through repetition, restraint, and attentive listening. I included the Cello Suites here because they mirror the spiritual life described in the Gospel — not dramatic, not loud, but formed through small, faithful movements that, over time, shape the heart. Like these suites, the life of faith grows through simplicity, patience, and the quiet presence of grace •

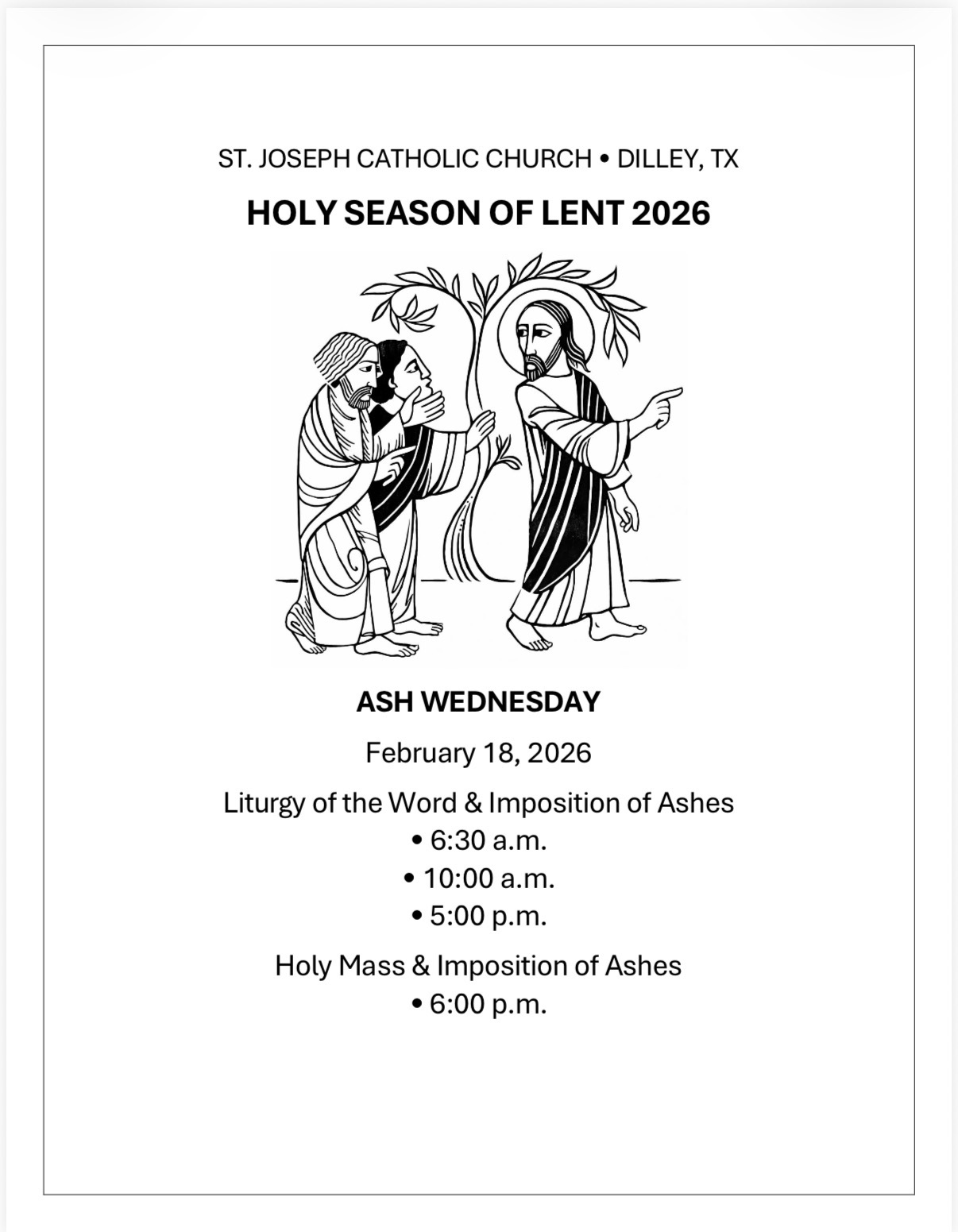

St. Joseph Catholic Church (Dilley, TX) • Weekend Schedule

Fr. Agustin E. (Parish Administrator)

Saturday, February 28, 2026.

5.00 p.m. Sacramento de la Confesión

6.00 p.m. Santa Misa.

Sunday, March 1, 2026

8.00 a.m. Sacrament of Reconciliation

8.30 a.m. Holy Mass.

10.30 a.m. Sacrament of Reconciliation.

11.00 a.m. Holy Mass.

II Domingo de Cuaresma (Ciclo A)

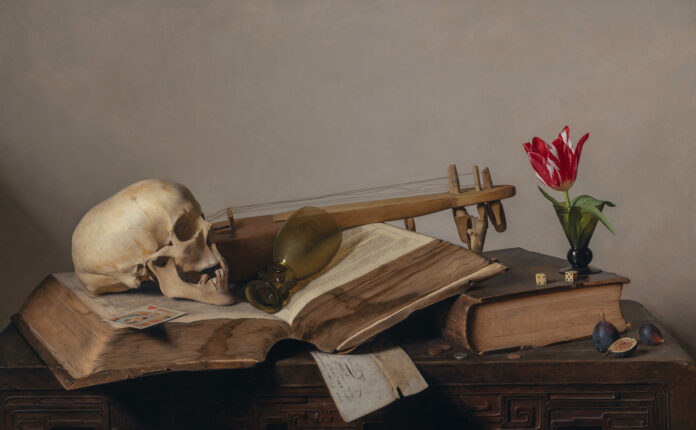

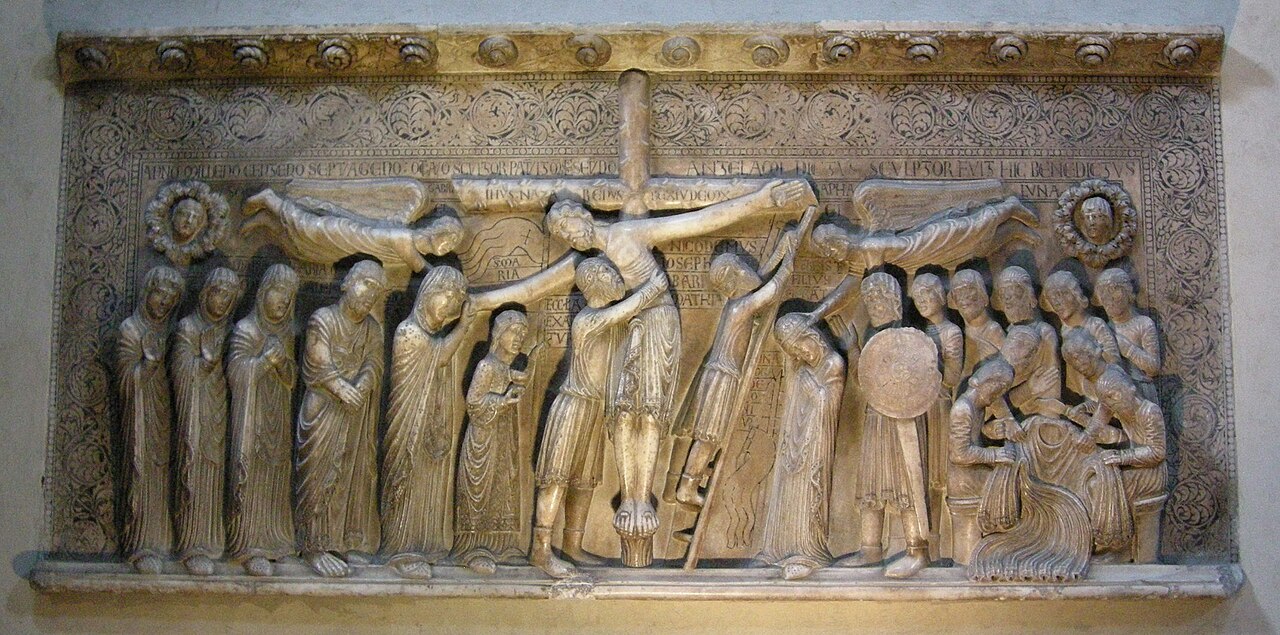

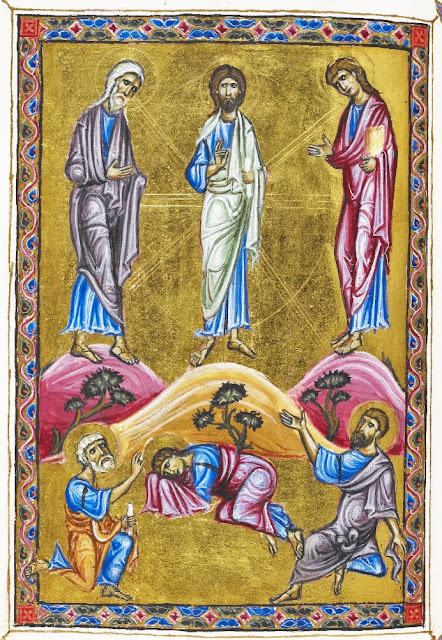

Basilius, La Transfiguración, ca. 1131–1143, manuscrito iluminado sobre pergamino, British Library, Londres.

A veces no es el ruido exterior lo que nos agota, sino la prisa continua con la que vivimos: pasar de una tarea a otra, resolver pendientes, sostener responsabilidades sin pausa. El Evangelio de la Transfiguración nos muestra a Jesús llevando a sus discípulos a un monte, no para huir del mundo, sino para detenerse y aprender a mirar con profundidad. Allí no reciben instrucciones complicadas; escuchan una voz sencilla: «Este es mi Hijo amado… escúchenlo». La experiencia no dura mucho. Deben descender y volver a la vida ordinaria. Pero algo ha cambiado: ahora saben dónde dirigir el corazón. La fe se fortalece precisamente en ese regreso cotidiano — en un momento de silencio antes de empezar el día, en una palabra paciente cuando el cansancio pesa, en un gesto discreto de ayuda, en un sacrificio pequeño ofrecido con amor. Como escribe Rainer Maria Rilke, la verdadera transformación ocurre en lo interior, silenciosamente, como quien madura sin darse cuenta. Algo semejante se percibe al escuchar el Cantus in Memory of Benjamin Britten de Arvo Pärt: una música austera y luminosa que, a través de repeticiones lentas, parece abrir un espacio de recogimiento donde lo esencial se hace audible. En medio del ritmo acelerado de cada día, la invitación permanece: detenerse, escuchar, y ofrecer a Cristo un pequeño momento. A partir de ahí, todo comienza a cambiar •

El Cantus in Memory of Benjamin Britten, del compositor estonio Arvo Pärt, es una pieza breve y profundamente meditativa escrita para cuerdas y campana. Construida sobre repeticiones lentas y una sencilla escala descendente, la música parece suspender el tiempo y conducir al oyente hacia un silencio lleno de significado. No busca impresionar, sino crear un espacio interior donde la memoria, el recogimiento y la trascendencia puedan emerger. Por eso resulta tan sugerente: nos recuerda que la profundidad no nace del ruido ni de la complejidad, sino de la quietud que permite escuchar lo esencial •

Lecturas para la Cuaresma