E. Hopper, Nighthawks (detail) (1942) oil on canvas, Art Institute of Chicago

There is a scene in Dostoevsky’s The Brothers Karamazov where Father Zosima, the elder, speaks of the power of the spoken word: «A word is a great thing, it can bring life, it can destroy, it can set the heart on fire.» The Gospel this Sunday, taken from Luke 6:39-45, brings us into a similar reflection. Jesus reminds us that the mouth speaks from the abundance of the heart. If the heart is filled with truth, love, and grace, its words will bear fruit. But if it harbors resentment, pride, or hypocrisy, its speech will betray it. The Book of Sirach (27:4-7) gives us a striking image: just as a sieve separates the husks from the grain, so too do words reveal what is truly within a person. Our speech is never accidental; it is the overflow of what lives deep inside us. This is not just a warning but an invitation. If we want our words to bring life, we must cultivate our hearts with the wisdom of God.

One of the great tragedies of modern society is how speech has become careless, divisive, and at times even destructive. We live in an age where words are thrown like stones, whether in personal conversations or in the anonymity of the digital world. And yet, the Church has always seen speech as a sacred act. St. John Paul II, in his apostolic letter Tertio Millennio Adveniente, spoke of the need for a purification of memory, a renewal of the way we speak about one another, so that history may be marked by reconciliation rather than division. If this is true on a large scale, it is even more urgent in our personal lives.

Consider the Requiem by Gabriel Fauré, one of the most serene and hopeful compositions ever written on death. Unlike other requiems, which emphasize fear and judgment, Fauré’s piece is filled with gentleness and light. The music itself speaks of trust in God’s mercy, of a soul that finds peace rather than terror in the final judgment. This is what happens when the heart is purified: even in the face of death, it can sing a song of hope. Our words should follow the same path—not words of condemnation, but of clarity, truth, and love.

Jesus warns against hypocrisy: «How can you say to your brother, ‘Let me remove the splinter from your eye,’ while you yourself do not see the beam in your own eye?» This is not simply an accusation; it is a call to humility. We are all tempted to judge others without first allowing God to heal us. The saints understood this deeply. St. Francis of Assisi, in his famous prayer, did not ask for the ability to correct others, but to be an instrument of peace, to console rather than to be consoled, to understand rather than to be understood. Words that bring life come from a heart that has been touched by grace.

In the end, the question we must ask ourselves is simple: what do our words say about our hearts? Do they reveal a spirit shaped by the Gospel? Do they build up the Body of Christ, or do they tear it down? Just as a good tree produces good fruit, so too does a heart nourished by God’s presence produce words that give life. As we enter into this Sunday’s liturgy, let us ask for the grace to let our words be purified. May they be words that heal, words that strengthen, words that reflect the mercy and truth of Christ. For in the end, our words will not just be a testimony to others—they will be the measure by which we stand before God • AE

St. Joseph Catholic Church (Dilley, TX) • Weekend Schedule

Fr. Agustin E. (Parish Administrator)

Saturday, March 1, 2025.

5.00 p.m. Sacramento de la Confesión

6.00 p.m. Santa Misa.

Sunday, March 2, 2025

8.00 a.m. Sacrament of Reconciliation

8.30 a.m. Holy Mass.

10.30 p.m. Sacrament of Reconciliation.

11.00 a.m. Holy Mass.

VIII Domingo del Tiempo Ordinario (Ciclo C)

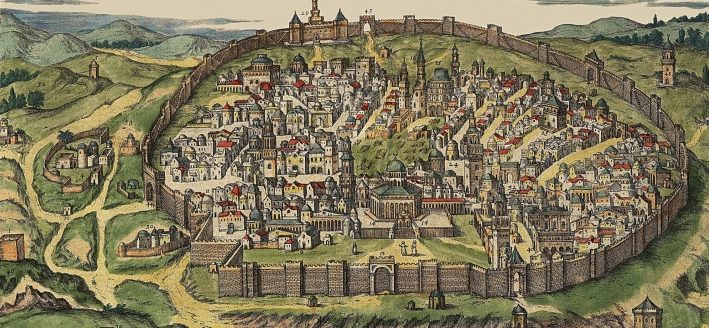

En este cuadro de El Greco titulado La curación del ciego la luz y la sombra juegan un papel esencial. No solo se trata de la sanación física, sino de un paso de la oscuridad a la claridad, de la ceguera a la visión verdadera. Es una escena profundamente evangélica, que nos recuerda las palabras de Jesús en el Evangelio de este domingo: «¿Acaso puede un ciego guiar a otro ciego? ¿No caerán los dos en un hoyo?» (Lc 6,39).

El Evangelio de Lucas nos invita a la autoconciencia y a la humildad antes de querer corregir a los demás. Jesús nos habla de la viga en nuestro ojo antes de señalar la paja en el ojo ajeno. Es un llamado a la autenticidad y a la conversión sincera. Si no cuidamos nuestro propio corazón, si no examinamos nuestras propias fallas, terminaremos guiando mal a otros, cayendo nosotros mismos en el hoyo de la hipocresía y la soberbia. El libro del Eclesiástico lo confirma con una imagen agrícola: «El fruto revela cómo ha sido cultivado el árbol» (Sir 27,6). La boca expresa lo que hay en el corazón, del mismo modo que un árbol bueno no puede dar frutos malos. Esto nos lleva a la pregunta esencial: ¿qué estamos cultivando en nuestro interior? ¿Qué palabras salen de nuestra boca?

El Papa San Juan XXIII, en su diario espiritual, anotó una vez: «Antes de juzgar a los demás, tengo que examinarme a mí mismo y corregir mis propias faltas. Solo desde la misericordia puedo hablar con verdad». La Iglesia siempre ha entendido que la corrección fraterna no es cuestión de orgullo o de justicia personal, sino de amor y de responsabilidad comunitaria. No se trata de ser ciegos frente a los errores, sino de mirar con claridad, con un corazón sanado y dispuesto a la compasión. Este pasaje evangélico nos invita a recordar también la música sacra, que ha sido durante siglos un reflejo del corazón humano en su búsqueda de Dios. El Magnificat de Bach es un canto de humildad y de alabanza, donde la Virgen proclama la grandeza de Dios y la pequeñez de la criatura. En esta obra encontramos el espíritu de este Evangelio: solo el que reconoce su pequeñez ante Dios puede dar frutos de gracia.

En la misa de este domingo, la Palabra nos coloca frente a un espejo. ¿Soy ciego guiando a otros ciegos? ¿Soy árbol de buenos frutos? ¿Es mi corazón fuente de bondad o de juicio amargo? Que esta liturgia sea un momento para pedir la gracia de una visión renovada, de una conversión sincera y de una vida que dé frutos de verdad y de amor • AE

Some music for reading

Gabriel Fauré composed his Requiem in D minor, Op. 48, between 1887 and 1890. The choral-orchestral setting of the shortened Catholic Mass for the Dead in Latin is the best-known of his large works. Its focus is on eternal rest and consolation. Fauré’s reasons for composing the work are unclear, but do not appear to have had anything to do with the death of his parents in the mid-1880s. He composed the work in the late 1880s and revised it in the 1890s, finishing it in 1900 • AE