J. J. Tissot, The Prodigal Son (The Return) (1862), oil on canvas, Private Collection.

The parable of the prodigal son is perhaps one of the most misunderstood passages in the Gospel. Many focus on the wayward son, his rebellion, his squandering of the inheritance, and his eventual return. Others see the older brother as the central figure, the one who never left, the one who remained faithful yet felt overlooked. But at the heart of this parable lies the father—his patience, his longing, his radical mercy. Lent is a time of return. Not just a return to God, but also a return to ourselves, to our truest identity as beloved children. The younger son had to lose everything to understand what he had lost. It was not just his wealth, but his dignity, his place at the table, his belonging. Yet even in the lowest moment of his exile, something within him remembered home. That memory, however faint, was enough to set him on the path back. The father, seeing him from a distance, does something unimaginable for a man of his time: he runs. He does not wait for his son to kneel before him, to beg, to prove his repentance. He runs and embraces him before the boy can even finish his rehearsed speech. The love of the father is not transactional; it does not weigh offenses before deciding whether to forgive. His mercy precedes everything. It always has.

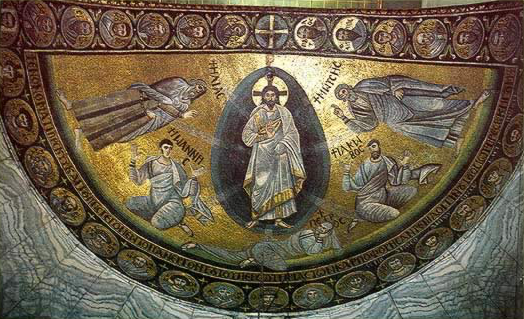

Perhaps what is most unsettling in this story is the reaction of the older brother. His resentment is familiar, almost instinctive. He has worked, obeyed, remained constant. He is the one who should be celebrated. And yet, when faced with the father’s generosity, he cannot rejoice. How often do we fall into this same trap? How often do we see God’s mercy towards others and feel that it diminishes us? But grace is not a limited resource. The love of God is not a wage to be earned, but a gift freely given. One of the most striking artistic representations of this scene is James Tissot’s The Return of the Prodigal Son. Unlike Rembrandt’s famous depiction, which focuses on the father’s embrace, Tissot captures the moment before—the son on his knees, the father extending his hand, the tension still present. It is a moment of decision. Will he accept the love being offered to him? Will he allow himself to be restored? The same question is asked of us. In music, Henry Purcell’s Hear My Prayer, O Lord echoes the cry of the soul longing for reconciliation. The repeated invocation, rising in intensity, mirrors the journey of the prodigal—from distance to nearness, from despair to hope. A parallel can be found in literature as well. In Les Misérables, the character of Jean Valjean experiences a moment similar to that of the prodigal son. Having been hardened by injustice, he encounters mercy in the form of a bishop who refuses to condemn him. That single act of undeserved grace transforms him completely. He could have chosen to remain in bitterness, just as the prodigal son could have chosen never to return. But the invitation to mercy is always there, waiting to be accepted.

Lent is not simply about penance; it is about rediscovering the joy of belonging. The prodigal son was not just forgiven—he was clothed, embraced, and celebrated. And so it is with us. God does not simply tolerate our return; He rejoices in it. The only question is whether we will take the first step home • AE

St. Joseph Catholic Church (Dilley, TX) • Weekend Schedule

Fr. Agustin E. (Parish Administrator)

STATIONS OF THE CROSS & SACRAMENT OF RECONCILITATION

Every Friday of Lent at 6.00 p.m.

(March 7, 14, 21, 28, & April 4, 11)

Saturday, March 29, 2025.

5.00 p.m. Sacramento de la Confesión

6.00 p.m. Santa Misa.

Sunday, March 30, 2025

8.00 a.m. Sacrament of Reconciliation

8.30 a.m. Holy Mass.

10.30 p.m. Sacrament of Reconciliation.

11.00 a.m. Holy Mass.

IV Domingo de Cuaresma (Ciclo C)

Rembrandt H. van Rijn, Return of the Prodigal Son (1668), óleo sobre tela, Museo de L´Hermitage (St. Petesburgo)

En el camino cuaresmal, este domingo nos invita a hacer una pausa en el rigor penitencial para vislumbrar el gozo de la reconciliación. La liturgia nos ofrece una de las parábolas más conmovedoras del Evangelio: el hijo pródigo, una historia de alejamiento y retorno, de caída y restauración, de justicia y misericordia entrelazadas en un abrazo. La parábola es, en el fondo, la historia de todos nosotros. En algún momento nos hemos alejado, hemos tomado nuestra parte de la herencia para dilapidarla en terrenos estériles, creyendo que la autosuficiencia es sinónimo de libertad. Pero la vida nos devuelve a la verdad: somos hijos, no vagabundos; nacimos para la casa del Padre, no para la miseria del exilio. Sin embargo, el corazón de la parábola no está en la caída del hijo, sino en el padre que espera. Un padre que, lejos de responder con resentimiento, corre al encuentro de su hijo, lo cubre con un manto, lo devuelve a su dignidad y organiza un banquete en su honor. Esta imagen nos revela el verdadero rostro de Dios: un amor que no humilla, sino que levanta. Como señala Henri Nouwen en El regreso del hijo pródigo, inspirado en la obra de Rembrandt: «Dios no nos espera con un libro de cuentas, sino con un abrazo. Su justicia es la justicia del amor que restaura, no del castigo que destruye.”

En este domingo, conocido como Laetare, la Iglesia nos recuerda que la Cuaresma no es solo penitencia, sino camino hacia la alegría pascual. La pintura de Rembrandt, El regreso del hijo pródigo, plasma el momento exacto del reencuentro. La luz se centra en el gesto del padre, cuyas manos —una firme, otra delicada— expresan tanto la autoridad como la ternura. El hijo, despojado de todo, se rinde en la humildad del arrepentimiento, mientras que el hermano mayor observa con frialdad. Esta escena nos recuerda que la misericordia no es siempre comprendida por quienes se sienten justos. La música también tiene su lugar en esta meditación. La Aria de la Suite para orquesta No. 3 en Re mayor de Johann Sebastian Bach es el sonido de la reconciliación. Su melodía serena y envolvente transmite la sensación de un regreso pacífico, de un hogar que nunca dejó de esperarnos. En esta Cuaresma, nos invita a confiar en la ternura del Padre. En la literatura, el príncipe Myshkin, protagonista de El idiota de Dostoievski, encarna una bondad casi sobrehumana, una misericordia incomprendida por quienes lo rodean. En él resuena la figura del padre de la parábola: un amor sin reservas, que desafía la lógica de la justicia humana. Como en el Evangelio, el verdadero escándalo no es el pecado del hijo, sino la misericordia que lo acoge. El Cuarto Domingo de Cuaresma nos recuerda que siempre es tiempo de volver. No importa cuán lejos hayamos ido ni cuántos errores hayamos cometido; el Padre no cierra la puerta. Hoy, la invitación es clara: levantarnos, volver y dejarnos abrazar. ¿Estamos dispuestos a entrar en la alegría del banquete? • AE

¿Algo para leer?