Francisco de Zurbarán, Agnus Dei, ca. 1635–1640, óleo sobre lienzo, 38 × 62 cm, Museo del Prado.

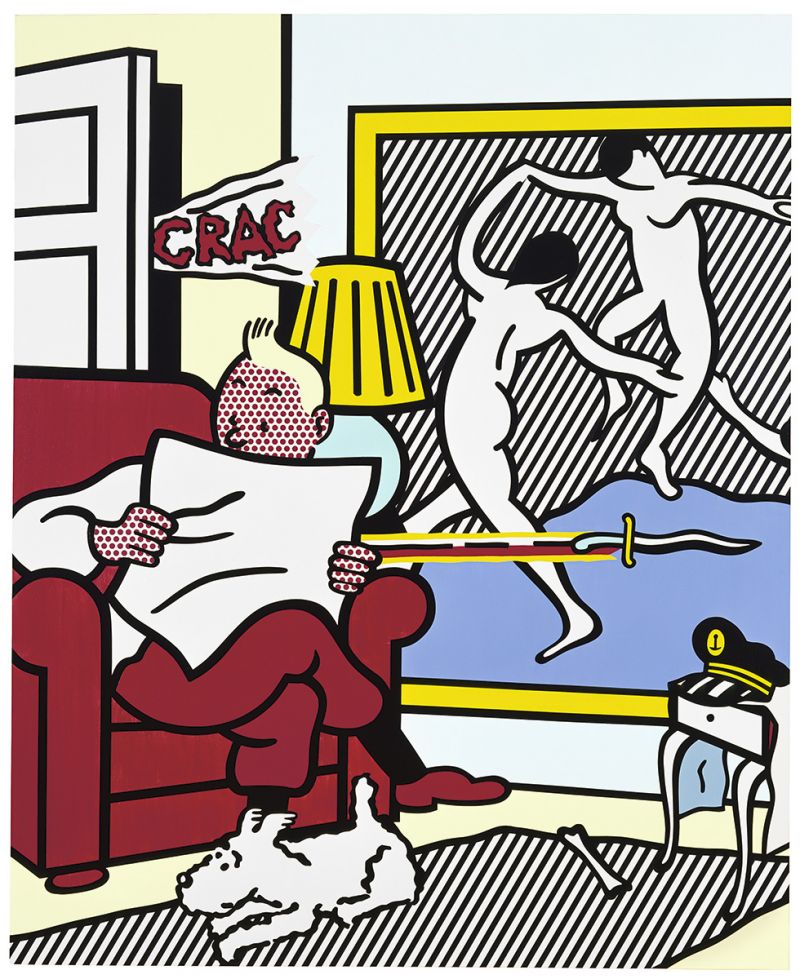

The light of Christmas has faded, the Jordan lies behind us, and the liturgical rhythm settles into something quieter. We return—briefly—to Ordinary Time, that stretch of days that comes before the long pause of Lent. And the Gospel does not rush us forward. It stops us with a gesture, a sentence, a finger pointing in the right direction. John the Baptist sees Jesus approaching and says with striking clarity: “Behold, the Lamb of God.” John does not hold the spotlight. He releases it. His entire mission reaches fulfillment not in being followed, but in stepping aside. With that single phrase, he names Jesus and quietly exits the center. What he offers is not explanation but testimony. Twice he insists, almost stubbornly, “I did not know him.” Faith, here, is not familiarity or control; it is obedience, attentiveness, waiting long enough for the sign to be given. And the sign is unmistakable. John sees the Spirit descend and remain. Not a fleeting emotion, not a spiritual high, but a presence that stays. This is how Jesus is revealed—not by claim or force, but by the quiet fidelity of God. Calling Him “the Lamb of God” reframes everything. Power will look like self-gift. Salvation will come through surrender. Even as the celebration of Christmas gives way to the ordinary flow of days, the Gospel reminds us that nothing about Christ is ordinary. From the very beginning, the cross is already inscribed in His identity. This brief return to Ordinary Time teaches us how to live between seasons. Like John, we are not called to shine, but to point. Not to possess, but to recognize. And to say, with honesty and restraint, as the days move forward and Lent approaches: There He is AE

Samuel Barber’s Agnus Dei is not music that explains itself; it asks to be endured, slowly. Written as a choral setting of his famous Adagio for Strings, it unfolds in long, suspended phrases that seem to carry the weight of a plea rather than a melody. What emerges is the Lamb of God not in triumph, but in offering—bearing, rather than resolving, the world’s sin. Like John’s words in the Gospel, this Agnus Dei does not draw attention to itself; it points beyond, inviting the listener to remain with what is given and to listen without haste • AE

St. Joseph Catholic Church (Dilley, TX) • Weekend Schedule

Fr. Agustin E. (Parish Administrator)

Saturday, January 17, 2026.

2.00 p.m. Quinceañera Celebration for Juliete Martinez

5.00 p.m. Sacramento de la Confesión

6.00 p.m. Santa Misa.

Sunday, Junuary 18, 2025

8.00 a.m. Sacrament of Reconciliation

8.30 a.m. Holy Mass.

10.30 p.m. Sacrament of Reconciliation.

11.00 a.m. Holy Mass.

II Domingo del Tiempo Ordinario (Ciclo A)

D. Bouts (ca. 1420–1475), Ecce agnus dei, ca. 1462–1464, óleo sobre tabla, Alte Pinakothek, Múnich.

Terminada la intensidad de la Navidad, la liturgia no nos empuja enseguida hacia algo nuevo. Nos devuelve, por un momento, a lo ordinario. Y ahí, sin estridencias, el Evangelio nos ofrece una escena decisiva: Jesús se acerca, y Juan señala. No explica. No retiene. Dice simplemente: «Este es el Cordero de Dios». Juan podría haberse quedado en el centro. Tenía gente, autoridad, prestigio espiritual. Pero entiende que su misión no es atraer miradas, sino orientarlas. Por eso insiste, casi con humildad desconcertante: «Yo no lo conocía». La fe no nace del control ni de la familiaridad, sino de la docilidad a lo que Dios muestra cuando quiere mostrarlo. Llamar a Jesús “Cordero” no es un título poético. Es una declaración fuerte. La salvación no vendrá por la fuerza, sino por la entrega. Desde el inicio de su vida pública, Cristo es nombrado a la luz de lo que dará: su vida. En estas semanas antes de que la liturgia nos conduzca a la Cuaresma, la Iglesia nos recuerda discretamente hacia dónde camina la historia. Quizá por eso este Evangelio suena casi como un gesto contenido, similar a ciertas músicas que no buscan resolver, sino sostener. Lo ordinario no es irrelevante: es el lugar donde aprendemos a reconocer dónde permanece el Espíritu. Y también donde aprendemos algo esencial del discipulado cristiano: no estamos llamados a ocupar el centro, sino a decir con claridad, cuando hace falta y sin ruido, ahí está • AE

La Misa Criolla, compuesta por Ariel Ramírez en 1964, nació en un momento de cambios profundos en la Iglesia y en la cultura. Fue una de las primeras misas en lengua vernácula escritas después del Concilio Vaticano II, y por eso mismo despertó entusiasmo… y fuertes resistencias. Algunos la criticaron por alejarse del lenguaje musical europeo tradicional, por incorporar ritmos populares argentinos —chacarera, carnavalito, vidala— y por hacer “demasiado cercana” una música que muchos creían debía permanecer solemne y distante. Sin embargo, su valor es precisamente ese: haber demostrado que la liturgia puede encarnarse en la cultura de un pueblo sin perder profundidad ni respeto, haciendo audible el Evangelio con la voz, la memoria y la esperanza de quienes lo cantan. La Misa Criolla no rebaja lo sagrado; lo traduce, y por eso sigue siendo una obra bella, honesta y profundamente orante •

lEcTuRAs pARa eL tIEMpo oRdinARio